This morning came news that the world appears to have just changed.

But even though this news is so big and so unfathomable that world leaders are stupified in responding, as I type, the presidential victory of Donald Trump in the US feels like an echo chamber of the B-word in the summer, here in the UK. All the polls said not to worry in the final hours, before a ‘shock’ result woke us up in the morning. This time, I am not weeping. I’m just a bit numb. Like lots of people around the world, I imagine.

It is, you might say, a symptom. The rise of a right-wing sounding reaction to the establishment. So is the numbness. Something is wrong, and a lot of people found a moment to finally express it. And express it mighty ugly. Perhaps mirroring how a lot of people really feel.

Much the same is said of drink culture. When under the influence, we let out who we really are. This should probably make me nervous about ever touching a drop – but on the rare occasions I slip from the lofty peaks of complete sobriety, I understand it looks generally ‘affectionate’. Thank goodness. But for thousands of us every single weekend across my home country it looks as ugly as a hellmouth, that desperate numbness.

And this is the lens through which The Light Side’s current feature sees the world – life in the nighttime economy on an average British Saturday night. And it’s hard to unsee. Especially when it’s actually filmed in the place where you live, the place you’ve always oddly felt safe from the madness of the rest of the world.

SALAD.

The same day I saw K-Shop for the first time, I recieved a Huffington Post article link from a writer espousing the joys of Bournemouth. Katherine Baldwin moved from Islington to the south coast last year worried, she says, that “it would feel like I’d retired before my time.” Those of us who live here forget that the rest of the country STILL hears the words ‘blue rinse’ when it hears the town name. You do forget. Not least of which because, as I’ve said before, who but young funksters have blue hair these days anyway?

I mention my little corner of the world often, because I feel strangely committed to the place where I grew up. Not because I completely never left, but because I’ve always oddly seen it through grateful goggles – goggles that see lifestyle, basically. Beach. And fresh air. And posibilities. And Katherine seems to be discovering what many say they’ve been finding and helping in fact to build over the last decade – a town slowly pulling together its potential. Potential to be a creative space to live and share ideas and make good things happen in. Slowly. Perhaps truthfully, rather than by exciting but unsustainable flash in the pan. Bomo will never be truly hip, but much feels like is happening here in some ways. And how jolly nice it feels for those involved.

A start-up like Yobu might illustrate this. A neat likeable brand and independent food offer on the high street that is aimed at younger people with a fresh, playful Jap-pop kind of futury vibe. Friendly. Happy. Tasty. A little different. And the place where bloodbath social commentary K-Shop was filmed.

CHILE SAUCE.

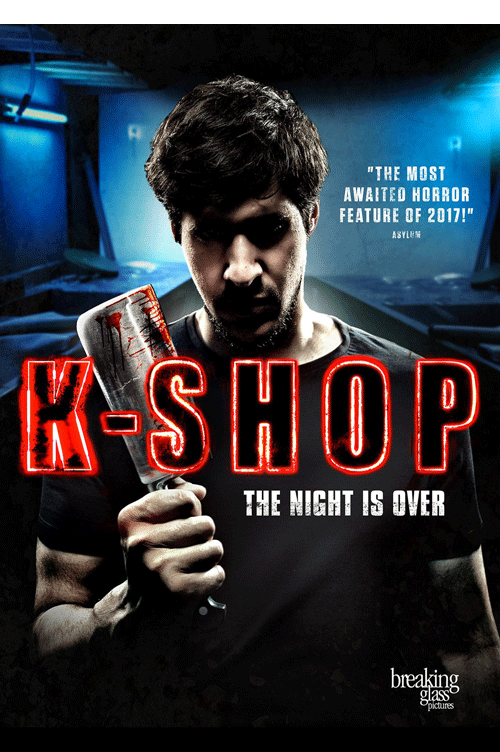

Screening the feature in the very basement in which its most grisly scenes took place was a bit odd, to say the least. And not least of which for writer/director Dan Pringle and Producer Adam Merrifield, the real duo behind the production.

“We spent six weeks in here” said Dan, “and I’ve not really been back. It’s… changed” he added, looking a little spaced-out as he took in the bubble tea graphics and beanbags.

K-Shop‘s tagline is the tidiest thing about it: ‘You are what you eat’. And if I describe the film as a dissection of the drinking culture that feeds the fast food industry at the weekend, I fear you may not at first take me literally. But you must. Cleavers are cleft. And doners are dealt. Messily. And you are left with the distinct impression that those meat grinders could essentially have ANYthing pushed through them and no customers would be any the wiser.

Billed as a clever horror flick, I’d say it isn’t that. It’s possibly just clever.

“The French thought it was a fantasy” says Dan. “We said ‘no, no – this is how it is over here’. And they were incredulous. The American’s just don’t get it. Everyone the length and breadth of Britain simply says ‘that’s our town’.”

Selling this film into foreign markets is an interesting multi-lensed mirror back to those of us watching it as Brits, who get the ubiquity of beer in our culture. Even more so, those of us watching it as Bournemouthers – who recognise every location outside the shop, staring quietly at street footage we understand is made up with some 70% of guerilla reportage. IE: Real.

“Those coming down for a night out see the town as disposable” says Dan. “They just use it once and throw it away. They don’t see the relentlessness of it.”

It may be a horror show to watch. But once you’ve had the odd grisly splatter that might make you smirk with nerves, just as you’re meant to with Horror, the film’s real tone grows over you like a realisation, or a film of grease, it is indeed more of a dystopian fantasy – a dreadful vision, which langurously paints a world at its own pace, in its own language. So criticisms of its lengthy running time and slightly ambling narrative, and of one or two plot points that might have seemed a bit unclear, these criticism feel – or felt to me at least – a little beside the point. This isn’t a type of film made by enthusiasts. This is its own thing – faced with grim determination by people who want to say something. Hold a mirror. One few of us would really want to look into.

But into which, perhaps now more than ever, we surely must look. Because if thousands of voters in many western countries this year rather dream of being able to describe their home towns as ‘discovering their potential’ and ‘jolly nice places to live’, then what do we do when even the jolly nice places have very ugly realities on display?

MEAT.

We all know it. You know it. I know it. I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. At half five on a Saturday teatime in town. Nightime in Bomo at the weekend is a freakshow. But it’s not a Bomo problem per se, it’s a Britain problem at least. And on the face of it the rest of the world finds it hard to understand why we live like this.

It’s a good question. The scenes of folk utterly degrading themselves, and of how those who run the kebab houses and takeaways deal with it every night like a moaning, drooling, splattering, face-eating front line in the zombie apocalypse. But as the film alludes, for a lot of those who find themselves running these little businesses, who have grown up in the UK but with recent family roots in countries all around the middle east, this ain’t trouble, mate. If you’d seen what we’d seen as kids…

Which begs the question. What is this decrading of ourselves a symptom of? From what are we trying to escape in the treadmill scamper towards endless Fridays – if escape for so many others was emigration and fast food businesses in other people’s countries. Making an okay living. If you factor in the monthly replacement cost of your shop window.

What are we so keen to blind ourselves numb from? Or even more chillingly, perhaps the question is: Just how have we set up the endless loop of living for the large weekend as a more distracting goal than something more… creative?

Is it a matter of economics? And if we put it this way, then how does such a dessicating view of human life really pump so much blood, and other fluids, into bar business? And onto the streets. What is it about weekly wage packet thinking that means our social starting point, our instinctive assumption, is that we must constantly look for little reasons to ‘celebrate’ – and this ‘celebration’ must always involve getting slaughtered? It’s the question at the heart of K-Shop.

Is it something so large, we mostly can’t see it? A cultural maw of mythical scale we can’t spot brooding under the high street. It feels oddly like there is something big breathing very slowly under this film. A thing we fear falling into so much we don’t even know it. Something that might even make us vote for desperate, pantomime characters, dressed up in comedy garb so incongruous they are grotesque. Monsters who will eat us, who in our delerium we desperately hope are our way out of the hellmouth we see ourselves in with clearer eyes. A culture so twisted, it in fact turns us into the very monsters we fear.

If trying to hold an academic human light up to the chaos of binge culture in the UK seems even more absurd than the inebriated playground antics of the Saturday night streets of Bournemouth themselves, then K-Shop is a bit absurd. It’s meant to be just a dark joke about a lot of joking around, isn’t it? But the film felt like rather more than that to sit through to me. It holds the attention because of some good film making – a richly grimy visual pace, an otherworldly aural/musical tone, a nice line in dark comic touches and a strength of presence in lead Ziad Abaza, playing the social science thesis-writing, kebab shop running, meatcleaving vigilante Salah with a disbelief-defying likeability worthy of a Marvel Netflix performance. But the integrity I felt running through the movie’s veins flows precisely because it wants to hold a lens up to something so deeply ridiculous and so profoundly serious. A culture based on getting blind.

What K-Shop does is focus the attention on it. And as we walked out of Yobu that night, into the very set of the freakshow we’d just seen – the walk back to our car through the town – it was impossible to disconnect from the film’s tone. A science fiction dystopia set right where we live, in a parallel universe we already live in.

Which does leave you feeling – as does so much of what we are seeing on our screens today – it’s impossible to know where terrible fantasy ends and terrible reality begins.

Perhaps it is a matter of where you look.

—