It is almost sixty years. Since the day the world first all looked up. So are you still gazing at your shoes with your headphones in?

If you’re someone who likes to keep their head in the clouds, or in fact, above them, then you might not be able to imagine a world before October 1957. The successful launch of the delicate little shiny Soviet sphere with alien antennae, Sputnik, effectively marked the beginning of the space age – the silver foil sales-boosting historic moment humans realised together that we might really be able to see ourselves reflected in the cosmos beyond our home planet. Space was suddenly no longer the playground of science fiction saps, but of leading edge science engineers. Grown-ups. And that relentless, cheerless beeping the first ever artificial satellite made may have popped a few bottles of Crimean sparkling wine kept on ice for the moment Sergei Korolev‘s rocket didn’t go pop before reaching orbit, but to many around the world I fancy it was oddly chilling. Not exactly cause for celebration. Pretty ruddy sobering, in fact.

Yet just over one decade later, the science and political will that this gravity-overcoming achievement combusted into the public consciousness around the world had sent humans all the way around the moon, to take perhaps the most significant photograph in human history. Earthrise. And that really should have changed everything. And maybe it did. Or rather, still is. Just a lot slower than millions of us expected it to.

Looking again at Apollo 8’s headbending image of our home planet as small enough, beyond the horizon of a cold lunar landscape, to be obscured by a human thumb, it makes me wonder how it has taken so long to feel the effects of that vulnerability of all human experience. And why no one has thought to put it as a symbol into the heart of a cultural festival before. Because it surely did change the way we see ourselves and where we live – so where the space has Bluedot been all our lives? Because if we ever needed a celebration of human possibilities and new ways of seeing ourselves reflected in our cultures, it is surely right about exactly bloody now.

CAPCOM

Carl Sagan coined the phrase “pale blue dot“, as you well know, sausage. The title of his 1994 book, he used it to discribe the image Voyager 1 took of its home planet in 1990 from the then-furthest point in the solar system any manmade object had traveled to before – some 40 astronomical units from the sun, 6,000million km from our parent star, just beyond Neptune at the time. And everything of us in that shot was just a, well, tiny pale blue dot. That was it. The ancient Greeks. The Roman Empire. The Ming dynasty. Vedic literature. The Koran. The Bible. The Renaissance. The Enlightenment. The split atom. Shakespeare’s sonets. Mozart’s Requiem. Bugs Bunny’s Brünnhilde. Einstein’s Relativity. Jeff Wayne’s War of The Worlds. I’m sorry I haven’t a clue. Love Island. All a single, smudged pixel in the background.

He’d had the idea, as yet another brilliant bit of human science storytelling, to turn the camera back towards us. Like the real purpose of the gold disks he’d also helped to curate, cemented onto the side of that very spacecraft, clicking the shutter on its long exposure camera. What would we see of ourselves from so very terribly great a distance?

Bluedot Festival evidently hopes it was – and yet will be – something inspiring.

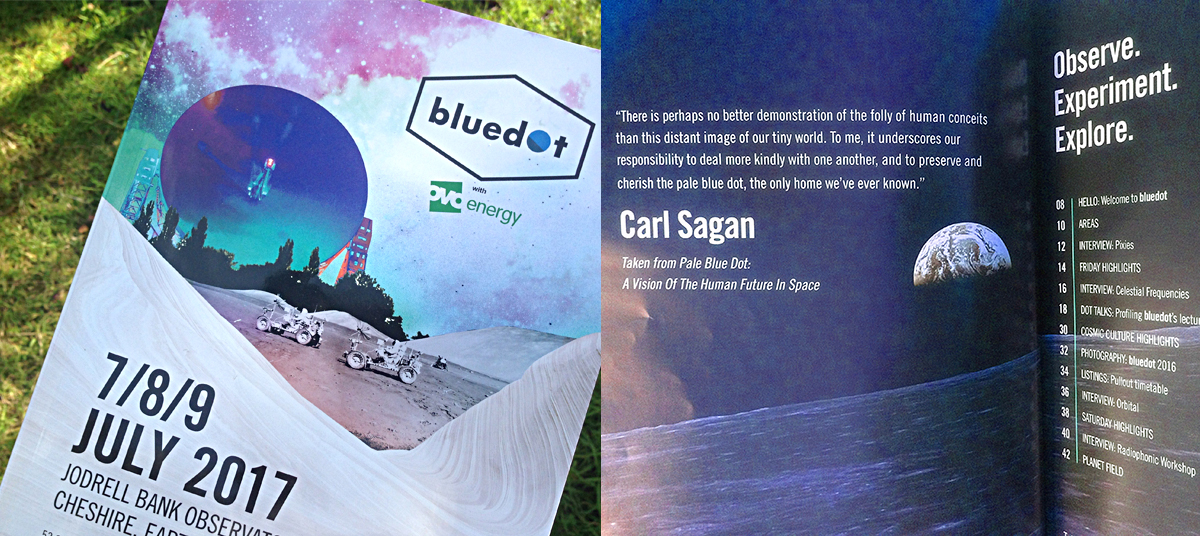

Because Bluedot Festival is, like a highly machined lens turned back on its audience as they gaze skyward, a celebration of music, art and science – collided together under the imposing visionary history of the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank in Cheshire – itself turning sixty this year. Y’darn straight. Right there. And right on the contents spread of the weekend’s brochure is a big fat pullquote from Sagan:

“There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Preach it. And take it to the goddam bridge.

Professors Teresa Anderson and Tim O’Brien from the discovery centre and observatory respectively at Jodrell Bank welcomed festivalgoers to a ‘stellar programme of music, science, arts, technology, culture, food and film” that represents the motif of scientific thinking that runs, they suggest, like a thread through so much of our culture today. The “many other scientists, musicians and artists” whose work they want their festival to celebrate. It is open minded. But suggestive. Dangling titbits of tantalising interestingness to the curious as they explore some fifteen spaces and venues around the pleasant campus of the observatory park.

As fellow creative pilgrim Lee said to our little band on the first day, “watch out for the entrance areas of these places – they’re honeytraps!”. And over the three days we camped together up in grounds of a legendary bit of science infrastructure – originally brought successfully online just in time to track Sputnik – I don’t think there was one venue we paused at that we didn’t get stuck at until the end of whatever accidentally fascinating talk or show was playing out there.

HIGHER FREQUENCIES

With Dot Talks on everything from epic to niche-specific views of the universe, the programme tempted our intense content mission planning with subjects such as Where is all the antimatter? and Space rocks on ice: hunting for meteorites in Antarctica and On you, inside you: the amazing and horrible world of parasites and The wonders of the Galaxy Zoo and Einstein’s Relativity: tested to the limit with pulsars or simply Humans in space: what’s next. It was impossible to really know where to start.

My crew for the weekend was perfect for a first exploratory away team to the festival. Writer, actor, broadcaster, musical muser and events producer Lee Rawlings, film director, writer, NASA geek and, it transpired, secret George Benson fanboy, Andy Robinson, urban design planner, art explorer, Chemical Brothers interpreter and the lovely first lady of Momo, Caroline Peach, and yours truly. What brought us together to varying degrees were significant appreciations of: music that loves sound and groove, conceptual creativity, human social/technical evolution, and of course science fiction. It’s hardly a wonder we all wanted to be there. Even if only half of us had some appreciation of camping. We all had some groove we wanted to be getting on, and we were all open to have our minds-equal-blown or fancies tickled by scientists, artists and performers. Obviously one of the first things we wanted to get to was The scientific secrets of Doctor Who. Sadly, I think disco of one form or another intervened and we didn’t make it.

I’d wanted to get to Steve Fuller’s Transhumanism: Can you afford to live for ever? or Tim O’Brien’s Hello out there – not least of which because his look at the story of the Voyager gold disks is soon to become very physically illustrated for both me and Andy, when the crowdfunder we both backed last year will deliver copies of the first ever vinyl editions of the probe records into our porches. We are still unsure if there are headline remixes included in the bundle.

In fact, perhaps one of the most especially Bluedot kind of talks might have been the arts-science panel for Cosmos. Because it illustrated the kind of connected thinking and follow-through problem-solving implicit with the festival’s manifesto.

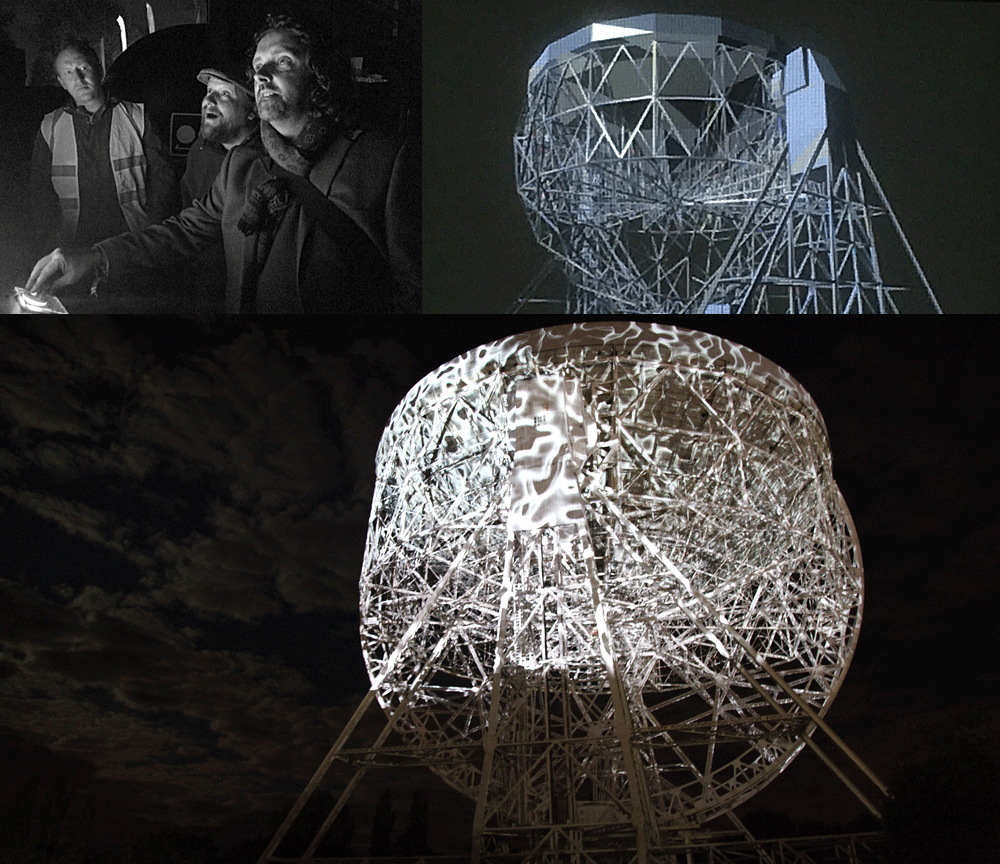

Commissioning art to make use of the Lovell telescope could mean any number of things. But it’s gotta mean big, right? In this year’s piece for the annual project, some five different team reps had to try to explain the stages of development necessary to turn a 1950s radio telescope into the funkiest, perhaps trippiest, piece at the expo. For, in engaging ‘Tokyo-based media artist, DJ and programmer’ Daito Manabe – the kind of utterly C21 influencer job title I long for – to bring alive the three thousand ton, sometimes nearly 90m high structure, the team at Jodrell Bank had to oversee a sequence of rather tricksy things.

In describing his response, Celestial Frequencies, Manabe himself shared his desire to use live data from the telescope to drive something interactive for an audience. And if a groovy way to use the physical structure’s presence in the grounds might be to projection map onto it, this meant that that giant laticework of metal had to be… well, actually mapped. Enter a LIDAR scanning team, from global developers, Arup. LIDAR uses lasers to precisely measure distances and can be used to scan objects into very highly detailed 3D models. So highly detailed, in fact, that the chap from the projection map team commissioned by Abandon Normal Devices processing the results held his head in his hands when it came to his turn to share their part of the process. “When we took the LIDAR team’s files,” he said, before looking up, “it was a, ah, big file to try to work with. We had to simplify it just a little bit.”

Their job was, in effect, to take Manabe’s algorithms and creative production and have them successfully talk to a viably runnable model of the complete telescope cradle and dish – one feeding into the framework of the other, to project back onto the actual superstructure with an interface ordinary schmos like us could twiddle with.

And after five teams’ co-ordination through a whole range of high-end technical and creative skills and a seriously long night the night before the festival?

The end result was, y’know, just a bit of cosmetic sound and light to the high passer-by. ..Wasn’t it?

But. To stand at the console at two in the morning, looking up at this behemoth of sensible science, and flick a roller dial around between pretty motion graphics, bending and striping the steel frame to pleasing sound design, was a dawningly striking experience, as you tried to take in that this giant disco feature you were mucking about with, twenty feet from the portaloos, was being driven by data streaming in from around the freaking cosmos.

In some goofy-stupid, festivalgoer fug, we were taking electrons spiraling around the electro magnetic field of our own galaxy, and background radiation from the big bang, and the relentless radiowave glitch of ‘LGM’s – pulsars – from other galaxies and mashing them up into audio-visual entertainment. Actual data. At my stupid actual fingertips. For fun. And for pretty freaky perspective.

I suppose not many would have said: “Chuh! My kid could’ve done that, mate” but it still goes to show that art’s ability to speak perspective shifting volumes mostly happens when its audience can appreciate its journey. But Bluedot is nothing if not playing to a crowd that just loves appreciating long journeys and pretty freaky perspectives.

MIDRANGE NOISE

This may be just as well, beccause dotted around the Dot Talks was a theme to really freak you out, if you had perspective enough. And this one might well faulter from playing to an already receptive crowd – because in the story of our relationship with our home planet, the only planet we currently have, the current act is playing out very ominously for its protagonists. And trying to sell a disaster movie as an arthouse doc is bad for boxoffice, to say the least. Not helped by the fact that disaster movies are meant to be schlock therapy, watching things blow up in the complete safety of a cinema. And arthouse docs tend to just make half-way clever-feeling people feel a little bit cleverer, or be reassured that they already know this. The screen keeps a distance as we paint the image of the world into our own heads.

So who on Earth could be prepared to really comprehend the possibilities of the whole world coming down upon our heads? And what to possibly actually do about such a thing? It’s very hard indeed to tune into an inconveniently existential truth. We wear ear defenders to that incomprehensible noise.

Because many of the talks’s speakers referred to one thing somewhere in their subject, sometimes with no editorial link to it – just a sense of responibility to mention it. The climate crisis.

Erik van Sebille‘s oceanography presentation was a more overtly ecological one – a calmly impassioned sharing of the plastics disaster unfolding in our seas. In practical terms, a whole other problem to worry about. But one I have been beginning to believe is a symptom of the same mindset driving the behaviours causing climate change. Van Sebille simply started with the facts: Of the 78 million tons of plastic waste humankind produces every year, one third is landfilled, one third is ‘recycled’ and one third goes straight into the wider environment. But a third of that recycled or downcycled waste ends up in the environment too. And that finds it’s way into the seas. Some five millions tons a year. Try to picture that.

Part of his work has been to help map the progress of plastic waste in the seas – the patterns of its drift in ocean currents. This has been done extensively with tracking buoys, and lead to fantastically simple and sobering online resources like plasticadrift.org which simply shows you where all the crap goes from any point on the planet. As van Sebille said:

“We can account for some 50trillion particles of plastic adrift in the oceans. But this number is way too small to cover the five million tons a year we know has been put in there. So where is it all? On the ocean floors, and in marine animals. I can tell you first hand, it’s getting pretty hard to find sea life that doesn’t have plastic in it.”

Plastic, he said, is pretty benign in itself. But it is made with other materials that are toxic, and it can absorb other toxins that get passed into the food chain. So the fact that it finds its way into so much marine life is, well… really not good. He pointed out that packaging for food is not all bad – “it helps reduce food waste significantly” he said – but it’s the uncompostability of it that pushes it into other chains of waste that end up in the sea. Tons of UK plastic is shipped to the Far East for sorting, outsourcing the problem supposedly, but in fact ending up, he claimed, in the hands of small family subcontractors that filter for items they can sell on before junking the rest in rivers.

“No one solution will sort out the scale of this,” he said in response to a plaintive audience question we were all dumbly thinking: What the freaking hell can we do? “It will take serious activation of a combination of responses – namely social economic solutions, chemical solutions and engineering solutions.”

When I then put my hand up and asked what one thing he wishes he could take back to audiences on land, in those visceral personal moments out at sea, he paused and said straight:

“Tackling the disaster of plastics filling up our marinelife food chain will mean nothing if we don’t tackle climate change fast. It’s all about that.”

Wow. How to dwarf your daunting problem.

And these were symptoms echoed strongly by Kevin Anderson in a swealtering Contact stage, later on. A former oil & gas engineer, he laid out some of the evidence for the climate crisis, with sixteen of the seventeen warmest years on global record having happened in the seventeen years since the turn of the century. And the news is bleak. As he put it, “What we need right now is a Marshall Plan scale of mobilisation” to bring the world’s carbon dioxide emissions down to anywhere near disaster mitigating levels. “And I just don’t see it happening” he said.

He spoke of the economic displacement of climate crisis responibility – the notion, as Naomi Kline refers to it, of stealing the sky. The idea that western industrialised countries effectively spent the carbon budget for everyone else, condemming generations of people predominantly in the southern hemisphere to fuel and environment poverty. In describing the sheer cost the UK, the US, the EU and others should be spending on climate crisis initiatives, Anderson simply said this:

“This isn’t mitigation. It’s reparations.”

Then he went on. “Every time you take a flight to a nice new holiday, picture yourself sitting down with your kids at breakfast. You just robbed them of a bit of their carbon budget. You are effectively saying you don’t care about their future.”

Difficult words that stuck with us. Do we indeed, as he put it, care enough? And are we culturally equipped to, any of us, really change?

Bluedot, though, is hardly a religious festival. It won’t turn new age any time soon and it shies from preaching. The modus is science – we are effectively encouraged to explore and piece the facts together of things ourselves. And more evidence of the perspective expanding work of the Dot Talks was found by Caroline and Andy in Robert Mulvaney‘s The hunt for the oldest ice on Earth in which he simply demonstrated the link between CO2 and planet warming. “This is a core sample from Antarctic ice” he said, holding up a long tube of said material. “It shows layers of time laid down, and captures some of the chemistry of the atmostphere then – because it literally contains the atmospheres of those different ages in the ice. Look,” he then said, “I’ll show you.” He then proceeded to hold the raw sample to the microphone so you could hear ice age air snapping and crackling free as it melted in the 21st century summer heat.

As he explains elsewhere, from his work as British Antarctic Survey science lead: “Trapped in deep ice cores are tiny bubbles of ancient air, which we can extract and analyze using mass spectrometers. Temperature, in contrast, is not measured directly, but is instead inferred from the isotopic composition of the water molecules released by melting the ice cores” And as the ice melted, the air bubbles popped and crackled their existence. Air not in the atmosphere for hundreds of thousands of years, released right there in a muggy, dried grass atmosphere of a culture festival tent. As Andy put it afterwards, “What he said, from analysing different periods of Earth’s atmosphere from the ice samples was that it is irrefutable that CO2 increases in the atmosphere and global warming are joined at the hip.”

Put together, it was more sobering than hearing Sputnik. But the strange web of different content we could explore created a constant background sense of wonder, despite the cold realities science can also present you with. Stepping into the coloured light and undulous squishyness of the Luminarium felt like therapy. Pottering in the arboretum at night between the flame light of Walk The Plank‘s primal torches, or the Kazimier‘s Night Chorus lazer blinking singing bots, or simply hugging one of Alison Ballard and Mike Blow’s humming Colony balls – we all felt the wellness that only exploration and play can give a human. It was either that or sob in a rocking corner unable to talk again. I think a lot of the evening’s visitors found it strangely hard to let go of those big glowing orbs.

“Bloody ball huggers” said one passer-by as we left.

And, honestly, the enthusiasm and knowledge of all those who spoke at the festival was simply infectious – it was impossible to really get a death grip on despair. Caught in the doorway of the delightfully engaging Professor Sarah Bridle, for example, as she explained the rudiements of dark matter and dark energy to a packed big top, I am sure we all became ever more convinced that Miranda could have had a richly educative element to it in the right hands. But she too, as Caroline reported back, shared elsewhere her professionally very separate personal exploration of sustainable food practices and the impact that the climate crisis will have on something so globally fundamental.

And all this mind expansion was before getting to the music.

DEEPER WAVELENGTHS

The musical emphasis, as I’d understood it rather deliciously for my own tastes, was to be on electronic music artists. Sounds like such a natural fight, right? Synth hero papa himself Jean Michel Jarre headlined the inaugural Saturday night mainstage last year. And, while this genre delineation was far from strictly true this year, there was plenty of experimental sonic joy to fall over as happily haplessly as the editorial content. Making a beeline for Leftfield’s complete live rendition of one of my all time favourite LPs, Leftism, I was lucky enough to find a couple of similar heroes of mine on the bill, with Goldfrapp putting in a jolly pleasant set. As well as a headline woofer-mullering from, at long last for me, Orbital – sonic legends of inspiration to me in the 90s. Watching a field full of old ravers with toddlers ringing the bell on their shoulders all night was rather spiffing, I have to say. As was the breadth of age range represented between them, loving the credible sonic intensity of a band formed 25 years ago.

But it was also the sort of place to discover Tubular Brass. If you’ve not heard of this orchestral project before, you will instantly have gotten the idea – Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells arranged purely for the swelling sound of the industrial north of England. Except that, Sandy Smith’s lovingly and skillfully re-arranged homage to the impossibly visionary 1973 LP is transcendent of casual ideas of the sound of brass bands, or of the immediate smiles the idea conjours. Oh, we certainly smiled through every segment of the complete parts I and II – especially as I had Rawlings mouth-trumpeting each motif with the exact knowledge of a true musical nerd in my right ear – but, collapsed there in the summer dry grass in front of the main stage, it was a very rich sense of smile I think we were feeling. One typical of the whole festival – of the joy of intelligence and heart and recognition all working together for just the right audience. Us.

We’d discovered Tubular Brass however because they were first on stage with a name that Lee had guided us enthusiastically towards that Saturday lunch time – Hannah Peel. Sharing her forthcoming LP, recorded with Smith’s 30-piece ensemble, Mary Casio: Journey to Cassiopeia, the sound was a joy to the tastebuds of my own ears, rather obviously. It draws instinctively I think on the big names of minimalism, perhaps especially Steve Reich in this project, though this headline is only a simple way in to describe its repeating, rising, morphing arpeggios of motif. But a sound squarely where you’d want it if you’re into such percussive use of melody. Synths are purposefully though restrainedfully front of house in the sound, making me a little weak at the knees, with a warm, potent width of trumpets, horns, bones and orchestral percussion gradually filling up the air around Peel’s richly clear arrangements. And yes, as of now ‘restrainedfully’ is a word. That natural fusion of clearly thinking both like a synthesiser lover and an orchestrator is simply gorgeous. And Hannah herself drops a splendid subtle friendliness into her wider work with her voice; dreaming as her music clearly is, she is nicely there with us in our listening and exploring.

Perhaps a name Hannah might one day be very used to hearing alongside her own is Anna Meredith. Why do I say this? It’s not simply that I happened to discover them both on the same exploratory, cosmic, creative weekend, or that they are both people with ‘anna’ in their names who clearly like sound. This would be silly. Maybe they will or won’t be doing a Back To The Minimalists! retro tour together in 25 years. But it’s some sense of sonic and structural adventurism that might ally them in the imagination just a little, different as their sounds are. And probably, I say with a little sigh in a way, the fact that they are technical-seeming composers and performers, knob twiddling as much as chart scribbling, who happen to be women. Now, old kitchen ravers and proggers like my merry band at Bluedot this July might casually imagine both these artists broadly sharing the generation of brilliant female musical explorers who’ve brought some nice arch pop into the mainstream over the last decade – Christine and The Queens, La Roux, Little Boots, Bat For Lashes and a good gang of others – but their work might be properly complete if no one felt the need make such very broad comparisons.

While it’s still a very good thing indeed to instantly see how much artists like Peel and Meredith will inspire, among many people, younger girls in particular towards driving musical sound for themselves and to going way beyond pop, encouraging them to stand confidently as fellow soundwave chasers, gear geeks and concept weavers… like so very much of now, here is to the day when not a single blogger wastes a paragraph describing such flimsy links. In the pantheon of art, may we cluster and mix without quick remarks about identity. But Vinita Marwaha Madill’s talk in the Star Pavillion may have illustrated a still relevant point, with How to be a rocket woman – starting from the premise that today still only 6% of engineers in the UK are women. So the work of inspiring diversity in talent pools is hardly over yet. My essential point is simply, hooray for the artists who stand out for leading.

And Anna Meredith really leads with her sound. What a sound, what a musical vision, and what a compositional resume.

The reviews and the commissions to her name mark her out as a significant artist of the early century. Why, so? It may be simply that she sounds like she’s chasing no other style but her own, from whatever rich mix of influences. Her structure of time, harmony and sound simply strike me as visionary. Where does such a boldness of decision making come from? I wonder this always when presented with any great artist younger than 100. But some minds do just arrive with a story to tell in a very particular voice – and they should be stars. She builds a sound with a very balanced use of her fellow band performers talents and I suspect she’d say it really was a collaboration. Starting with her own use of that great pop instrument, beloved of generations of kids dreaming of rock and roll, the clarinet, Anna’s arrangements have great oscillator throbs and ringmodded arps and fizzy twinkles beaten boldly around by Sam Wilson’s finely counted drums, and Jack Ross’s raw but metronomic electric guitar, augmented with Maddie Cutter or Gemma Kost’s tremming cellos, and stamped with arch art authority very firmly by the muscular blasts of Tom Kelly’s tuba. Yes. I may often say there are not nearly enough trombone solos in popular music – and I stand by this – but you know you’re in for a good time when the hippest looking member of the group is lung-pummeling sixteen coiled feet of copper-zink alloy tubing and valves. Opening as they did with the mesmerisingly take-no-prisoners arpeggiated reverse helter-skelter of The Vapours, my introduction to Anna Meredith felt like being knocked into a side universe where perception warping creativity and intelligence are just the normal language of music. I always imagined they were.

But the interlaced cross-using of the band’s talents served to underscore their apparent aim to give us a properly art-minded new way of musically seeing, with Sam’s vocals from behind the blattered toms – while still counting 17ths or some such witchcraft – managed to sound like something from the delicacies of the Kings Of Convenience. That Anna herself then smiles and chats with super friendly ease, like she’s simply any normal favourite mate, just wraps up the whole experience as perception shifting. And… inspiring. I feel foolish now for part-exing my clarinet for my first synthesiser; I clearly should have kept them both. Certainly in the mindul hands of Meredith, it makes for a perfect artist for Bluedot Festival.

If there is, of course, a band more perfect than the Radiophonic Workshop.

ANCIENT SIGNALS

With Rawlings and Robinson at our side, back in the sweaty Orbit stage, we really could not have computer selected a more appreciatively tailored audience to see this legendary company of sonic pioneers, formerly of the unique scores to all your favourite BBC science and adventure series. Because both of them could name check every member of the group. And point them out.

..Well I mean of course YOU could also name Mark Ayres, Peter Howell, Paddy Kingsland, Roger Limb, Dick Mills and Kieron Pepper – but you’re as highly specialised as them. I considered attempting to revive my ‘Did I tell you about the time I met Ken Freeman’ anecdote, but I felt it wouldn’t fly.

What really flew was, of course, the sound. Melifluously mighty. Effortlessly rich. Whimsical to a faultline of sonic tremours. And a beauteous thing to watch grandparent-aged English shed boffins make engineering poetic. When they finished by dedicating their finale to their missing compadre, Delia Derbyshire, wrapping up the show with the heavily Peter Howell-ed version of her sacred Dr Who signiature tune (my secret favourite version, the ‘disco’ one), there were tears. Because it was another moment, for some of us, of that central thing that Bluedot may have almost accidentally exposed. Like a raw nerve.

Recognition.

Symbolically, the Lovell radio telescope is there to observe. To listen. Sweet as it may have been for my homies to very kindly describe a thorough plan to:

‘hijack the Jodrell jack ports, plug in some Momo, and reverse the polarity, baby’

– to which I replied that it was sixty years old and we’d be lucky if it’s anything as new as a five-pin DIN on the back of the Lovell – that massive bit of astronomical infrastructure is there to recieve, not broadcast. That is perhaps partly why it is such an inspirational object – it doesn’t just physically impose behind the main stage like a super Martian tripod, it represents the opposite attitude to the seemingly predominant one of our current echo chamber age. Openness, curiosity and observation. Am I stretching the poetic conceit too far to suggest a confident smallness in the universe? Maybe. But I don’t think we would have been alone in feeling such emotive things when gawping at it.

Watching the age range around the campus, it was obvious that many Generation Xers were jumping all over the festival, just like us. Because it may represent some sort of nucleus of all we grew up hoping for – an enlightened sense of progress. Waking up from a mindless sense of consumer improvement to truly humanise our advances. Old utopianism, but with a heart.

The Green movement may have found true conscious form in the artistic reactionism to post war consumerism – the counter culture. An instinctive cry to make things more human, before we knew quite how this might really shape things for us scientifically. But practically, Green legislature was muchly laid down in the 1970s in the wake of all those festivals and records and protests and art, and conservationism filtered through the crooked limestone of old Albion’s popular culture to take hold of many young imaginations, when I was still in knee-length socks. But it got progressively drowned out by other desires and cares in the grimly economic ‘modernisation’ of my and many other western countries in the awkwardly adolescent 1980s – trading hippies for yuppies. Somehow the culture of my homeland made the dream of haunting sloany wine bars in shoulder pads and pastels less laughable than wanting to plant something rooted with earthly meaning.

And maybe it was this age group that most ‘got’ the festival. For all ages were actually represented, but many of the groovy millenials around us in the camp sounded like they were mainly there for the music. And a good music spread was indeed a great draw of a certain kind. But the idea of this being the case still seemed funny to me. Not simply because there are so many other festivals in the UK for musical hedonism, but because millenials have at their heart something my generation only carried as a seed, I fancy. At least, I have imagined this so much lately. A innate sense of connectedness. That Gaia, that bloody hippy holistic one-ness – they get it. In them, the seed is germinated. And lord knows they apparently like hemp enough. The digital network is as symbolic as it is practical, illustrating an instinct I see in my neices and nephews that everything is connected. Through the air, not an electrical cable. So who would want to live in a stuffy box?

Yet. Where are the outlets for them? Is the post-yuppy aenesthetising of my generation’s childhood love of nature perpetuating that world of crappy silo thinking? It’s been my supposition lately that in drilling airholes in those boxes, we have allowed our children to see the outside connected world without unlocking the doors to let them out into it. I wonder hard if they so often have alien levels of anxiety at young ages not simply because of the freakish social high wire act they are expected to perform between the hyper personal and the physically distant; suspended as they too often seem to be above the benefits of the healthy practical human balances of the local community. But because they have an instinctive expecation to live lives that are connected, meaningful and sustainable, while being shown few everyday systems to facilitate this. They expect everything drone delivered but want those products and images on Instagram to mean something more than empty perfection. They are the most stressed out by comparing themselves to each other and the most loveably socially liberated generation in centuries. They live on truly terrible food from sun up to bedtime and will reduce a festival field to a wargrave of plastic and rubbish like consumerist locusts, yet are forehead-smackingly disbelieving of climate crisis denial. They hope for jobs that will pay them to be special, but they want to do more than push money around without meaning. You’d think Bluedot Festival would be the cry of connection to the twenty-somethings of 2017.

Perhaps, it will grow to be so. As the lovely first lady of Momo said, two of the talks she made it to were packed with folk in their twenties, wanting to know more of two very pertinent sounding issues for the evolving twenty-first century – Geoff White’s talk The dark web and Robert E Smith‘s The banality of Artificial Intelligence. “Both had queues overflowing from the venue,” she said, returning from the Contact stage. “The AI talk really stuck with me, because he was trying to highlight the misnomers of it. That there are still biases that creep into the coding – we don’t have true artificial intelligence by a long way yet but, something more concerningly dumb that we are getting used to interacting with. Rubbish in rubbish out still applies when developing these bots.” Then she added: “He said we need to be trying to develop AI that is like Data, not Lore!” While a Star Trek TNG reference might be very unmillenial, AI and robotics and the future of work are generally hotbutton topics in the mainstream now, and I wonder if youger visitors who came this year for the music will find themselves returning to Bluedot more specifically to hear about the deeper editorial topics that will affect their lives in a radically evolving future.

I couldn’t help taking delight in seeing so many younger children running around in the sun between bouncy art installations, lever-pulling science experiments, space agency debreifings, oceanography films and sonic cathedrals of exhilaration. For them, all this stuff will go together like it’s supposed to – naturally. Like it’s normal to jump around with your heart full to music that sounds nothing like the bland cookiecutter pop of commercial radio, while thinking about the 40,000 year old air you heard popping from an Antarctic ice core sample half an hour before, under the shadow of a structure built to listen to the song of the cosmos. It brings me to tears again, thinking of it.

But I am a silly old utopian at heart. Rewatching Star Trek and The Next Generation lately, I have almost been in tears at it’s stagey moralising nearly every ep. I suspect I may be bringing a lot of me to much of this. A symptom of the creative project I have been working away at for the last two years and which has changed my outlook on the world. A project I can’t help thinking would singlehandedly find its audience at Bluedot Festival. Music, art and science. Curiosity and playfulness. Hope.

As one person simply just stuck her nose in and said to Andy and I, in a coffee queue late one night, “we want the talks.” We were discussing the queues to the rich array of lectures and how, in a way, the proximity of some of the music venues to some of the Dot Talk venues was distracting. This festival goer agreed with us that the real source of inspiration was the knowledge and debate and exploration – the music was more like a brilliant celebration of this.

It made me feel there was just one thing missing. An actual preach.

A doggone, God’s-honest rally cry.

Something very unscientific. And probably just way more of me I am projecting there at the moment. But with such a raison d’etre to its very name, it seems to me that the main stage should surely be hosted – at least for an opening and closing party – by champions of the glorious sweet spot where artistic and scientific social endeavour intersect. Helping its audience feel placed into the story Bluedot wants to help tell, to amplify, to broadcast. Because these are times to tell new stories and create new ways of seeing, the like of which we haven’t needed in generations.

A talk that struck a chord with all four of us, Andy had homed in on instinctively. New Scientist‘s Catherine Brahic – Stone age cinema. Why would all four of us feel the resonnance of hearing about neolithic cave art, you may ask? Well, it will become obvious when Andy and I reveal what we’ve been developing together over the last year, and how much it’s filled our minds together at home and with our families. But his instinct to investigate some human creative origins while considering the human future gave Catherine Brahic’s insightful findings a moving clarity for us, as she shared a fresh look at the possible real intentions of cave artist storytelling 40,000 years ago. What it sealed in our minds over the whole weekend was the need for a true human connection across everything of now. A true human storytelling.

In the perfectly chosen setting of Jodrell Bank Observatory, with its elegant, giant ear to the heavens, I’d say the organisers know that the greatest story tellers aren’t carnival evangelists. That the truly faithful don’t shout the mind of God – they are listeners, carefully cupping an ear for the still small voice of truth. Resolute in learning to tune out the background static. The BS.

Bluedot Festival may not want to preach. But we were converted. Or maybe just identified. But I’d like to think it could be a festival from which people feel activated – some sleeper cells triggered to consciousness. Because, for us, this was a shared moment and a cultural idea that, for all it’s don’t tell, show, was saying a very great deal, very clearly indeed.

How confident will it be in trusting its own story into the future, I wonder? As thoughfully engineered as it already is, even groundbreaking, perhaps it is still just putting out searching signals at the moment. But I sincerely hope it is just clearing its throat.

Because when it really sings, we may all be celebrating.

MOMO:TEMPO REVEALS THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO HUM >

In a unique one-off show, Five Songs to help us Unsee The Future, Timo Peach and Andy Robinson unveil their creative challenge to the Now of fearsome realities

A GOLDEN MOMENT OF ART AND SCIENCE >

The bloke from Momo unwraps a very special gift, to change the way we hear the cosmos and see ourselves.

OUT OF THE CRADLE >

Watch Andy Robinson’s beautiful short film celebrating a unique moment in human history.

“That central thing that Bluedot may have almost accidentally exposed. Like a raw nerve. Recognition.”

—

Thank you for this extensive report on Blue dot. I had no idea this existed. Your comprehensive report on all of the elements involved as well as your personal slant was engaging and fascinating. It certainly peaked my interest I would love to have been there. I was at Cargo Valise Noir however and it was truly original and a wonderful experience.

Oh thankyou so much, Norma. Yes, although Cargo seemed to be very much looking back through heritage, for me it was absolutely connected to the other projects I’m working on, and to the centrality of thinking similar to Bluedot’s. Heritage is really a looking forward thing, and a human connection thing – and what is our story of the sea if not one of voyaging endeavours? Like trying to reach the stars. It’s all connected in my head. So thankyou for getting it. x